Oblong Multi-user Multi-modal Spatial Operating Environment

The Frontier of Spatial Computing

Before spatial computing became a buzzword, Oblong Industries was already building it. Founded by Minority Report’s science advisor John Underkoffler, the company’s vision was simple but radical: replace the flat, single-screen paradigm with a living 3D operating environment that understands people, space, and movement.

As Director of Interaction Design, my focus was to make that world usable — to give form and feeling to computation in physical space. I led the design of expressive gestures, interaction systems, and visual feedback models for g-speak™, Oblong’s spatial operating environment.

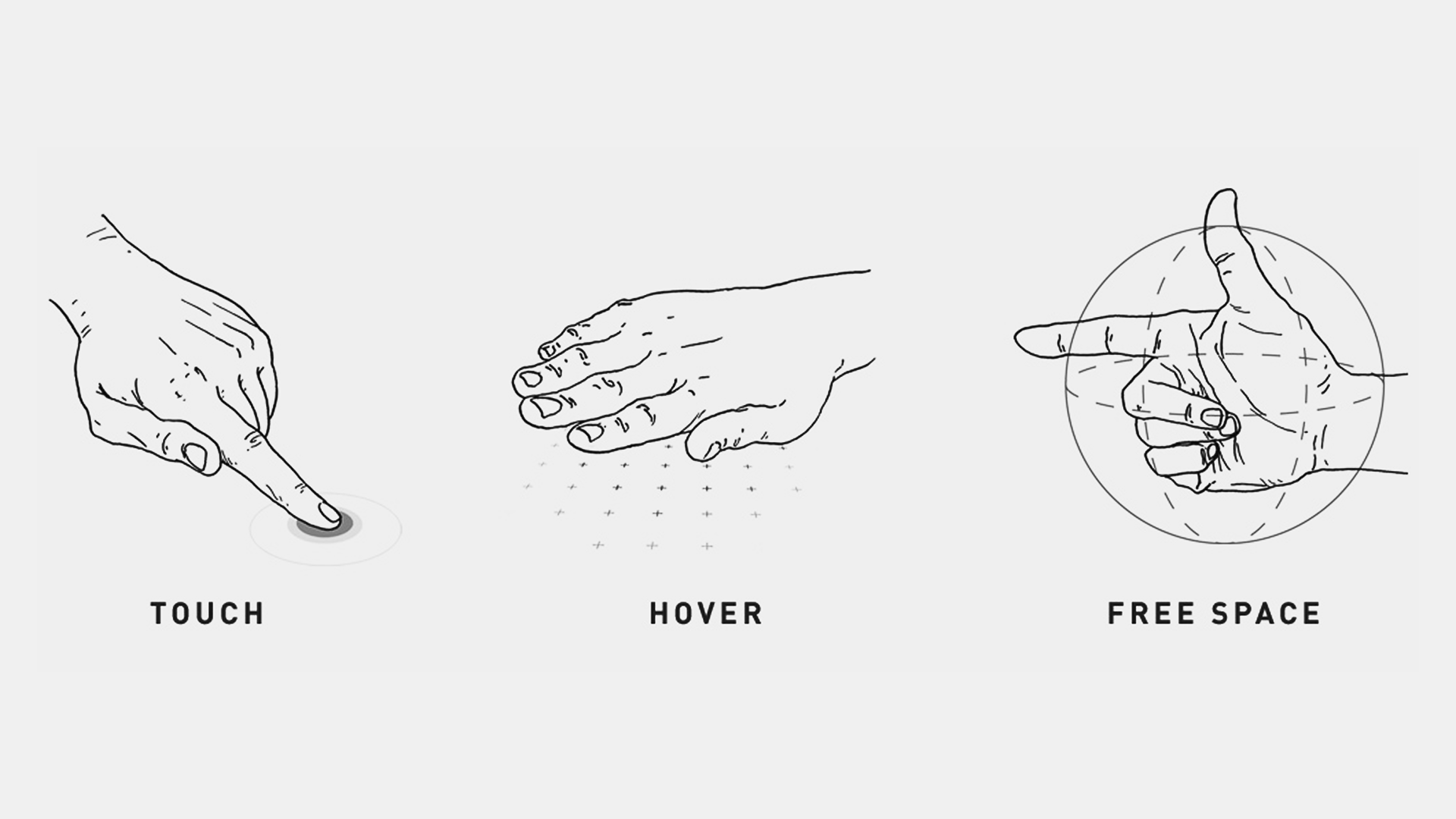

Designing a Language of Movement

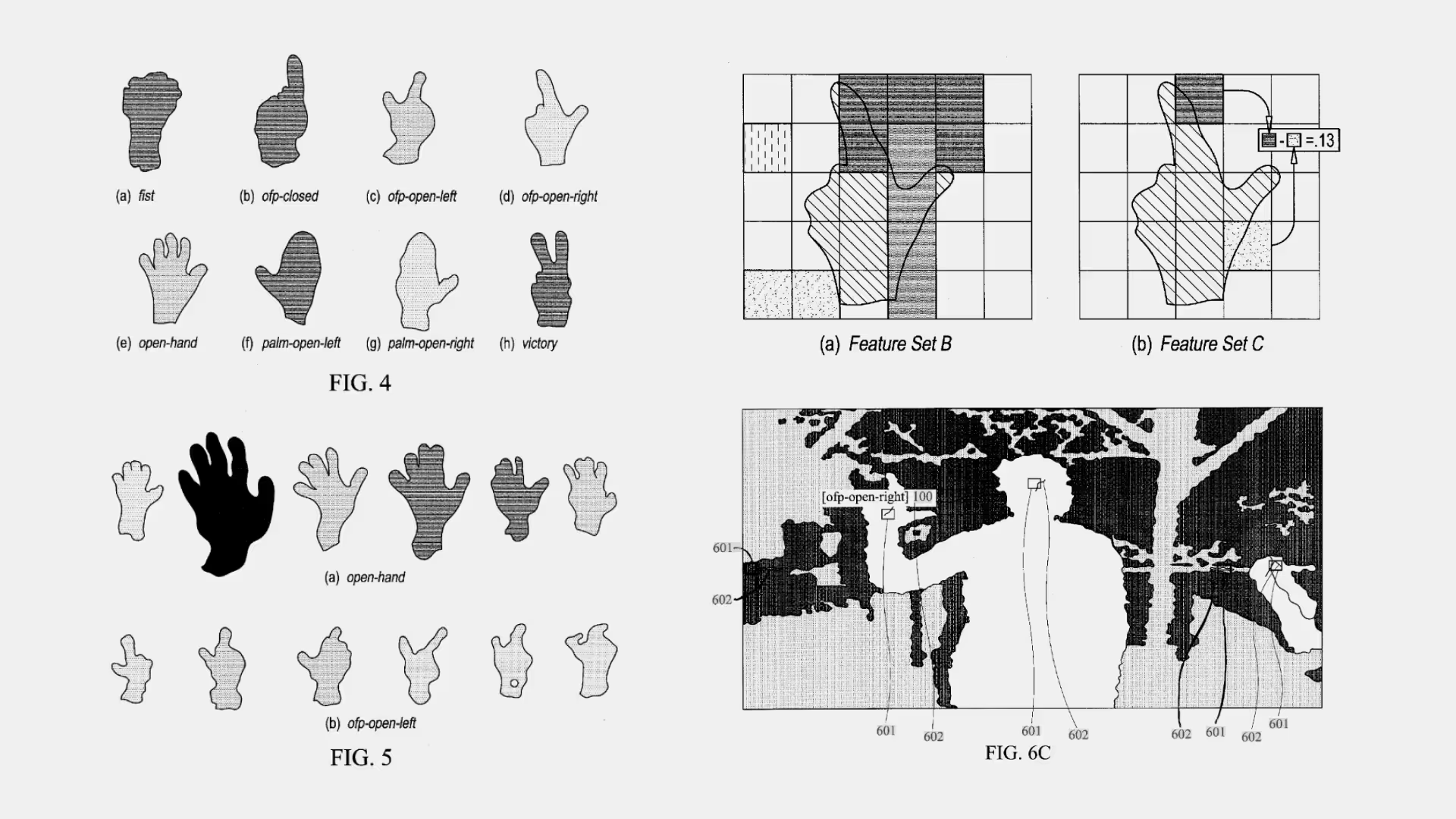

At Oblong, gestures were verbs. Pointing, reaching, and sweeping weren’t gimmicks — they were grammar. My work involved developing this vocabulary: defining how gestures looked, felt, and communicated system state.

We learned quickly that motion has to mean something. Gestures need rhythm and responsiveness; feedback needs to be alive, continuous, and ambient. I created interaction models where success and failure were visualized through motion rather than icons — where even subtle animation could convey intent, confidence, or ambiguity.

This design language became part of the company’s patent portfolio, including two gestural patents developed in collaboration with our research and engineering teams.

Oblong's Greenhouse SDK for spatial prototyping

US Patent 13/909,980 — Spatial Operating Environment (SOE) with Markerless Gestural Control

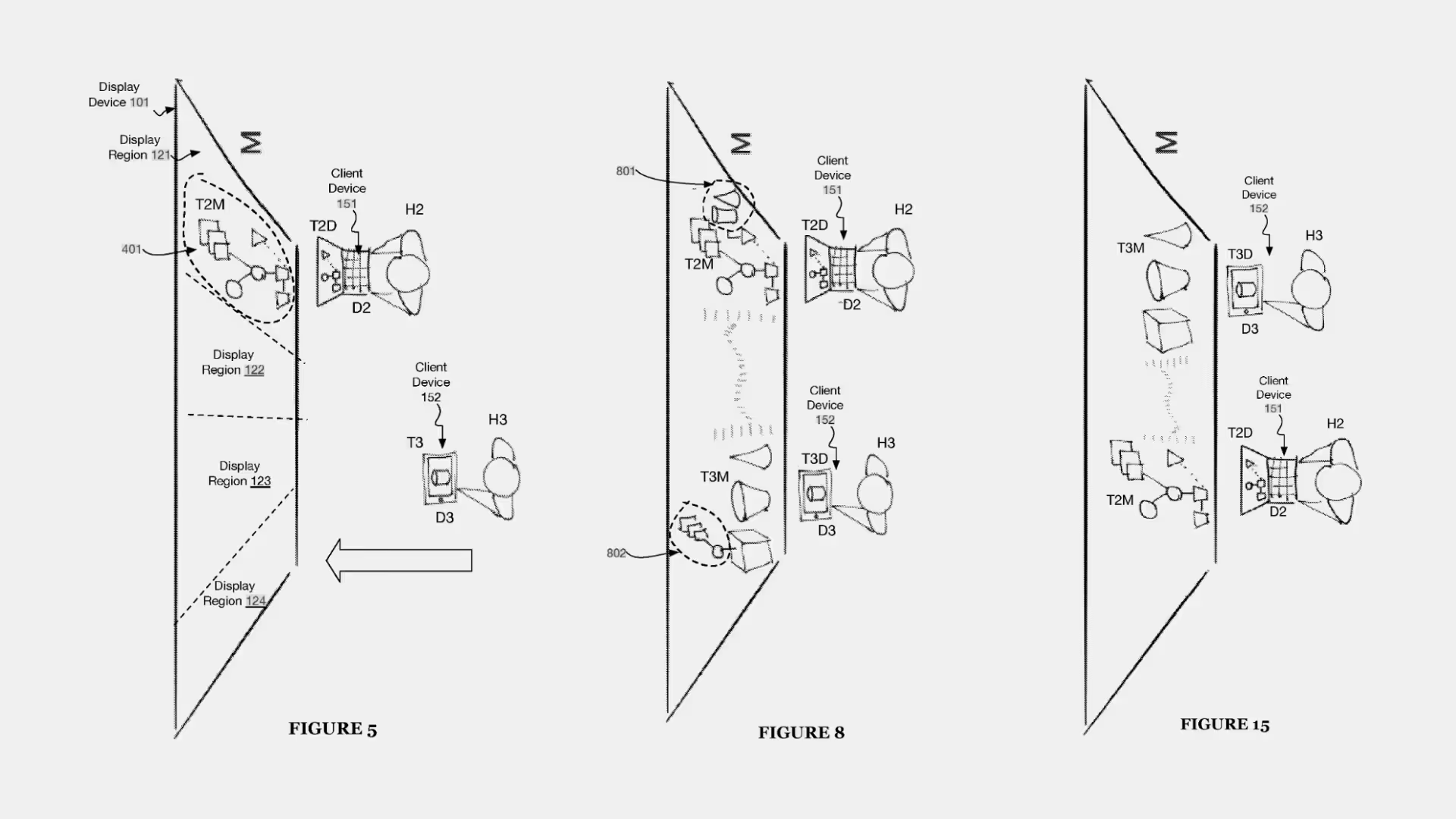

US Patent 15/643,264 — Spatially mediated interactions among devices and applications via extended pixel manifold

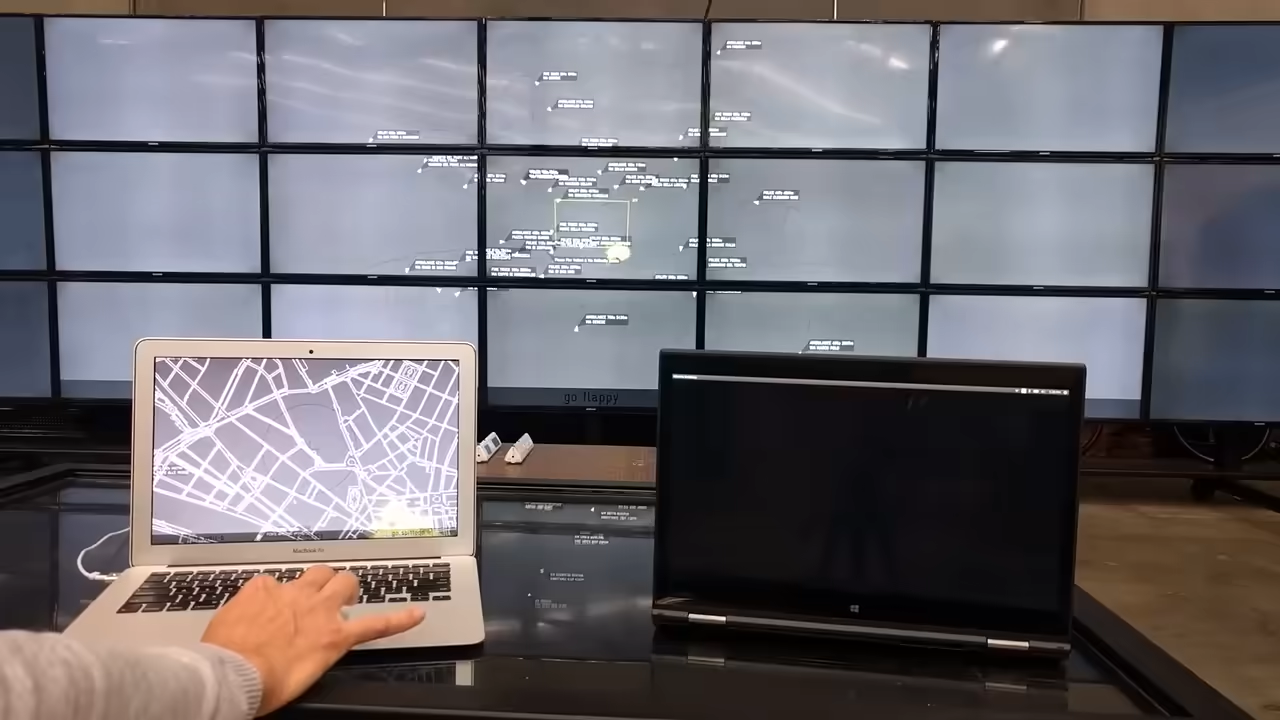

Multi-user, multi-modal input disaster response coordination

Rapid Prototyping as Research

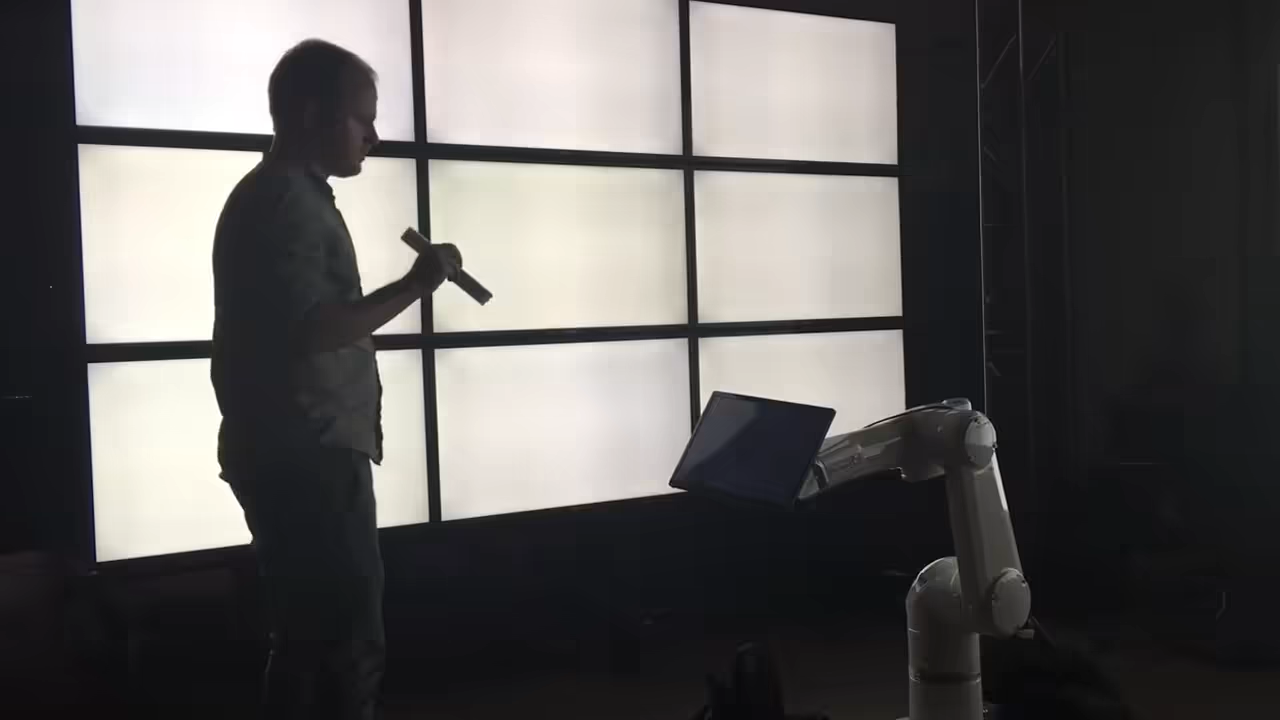

Oblong’s design process was deeply experimental. Every idea lived first as a prototype — physical, visual, or spatial. I built tools that visualized 3D gesture recognition, simulated multi-surface environments, and stress-tested our motion feedback system.

Some prototypes lived only a day; others evolved into full production features. The emphasis was always on velocity: testing interactions as quickly as they were imagined.

Botty McBotface

Oblong hands

g-speak + Looking Glass

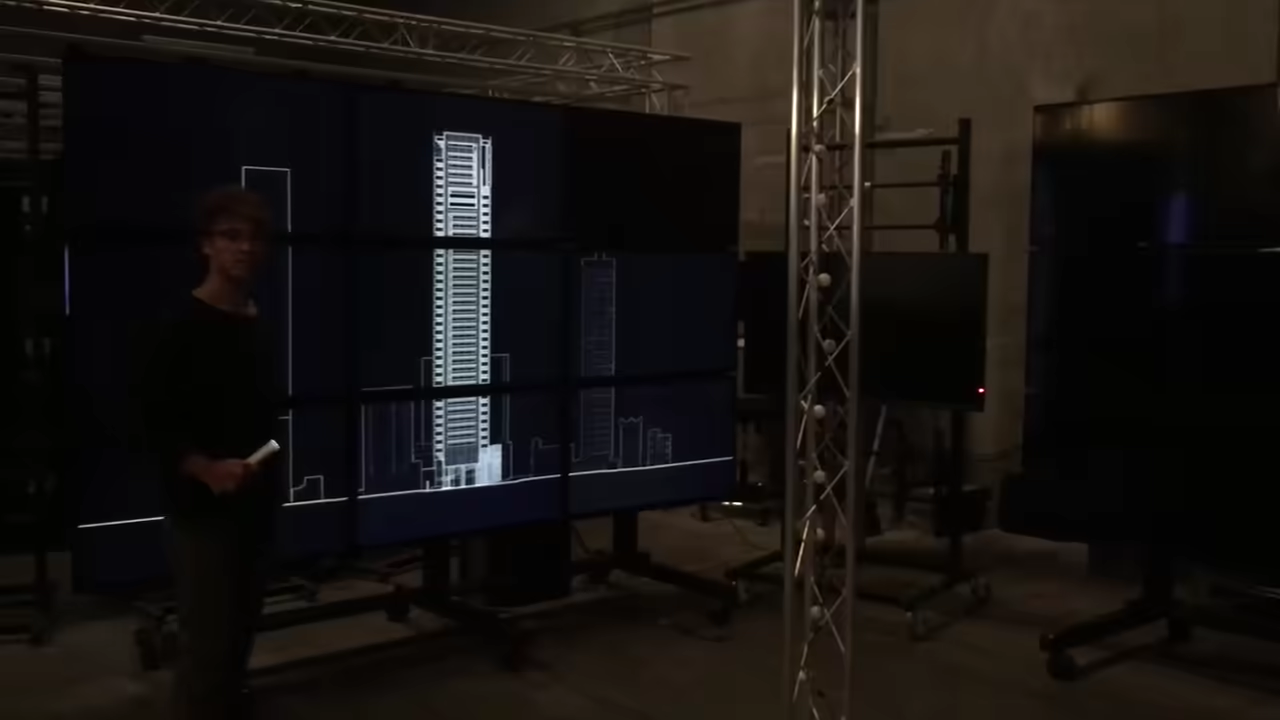

Scraper prototype: Real-world coordinates as architectural input

Human Systems in 3D

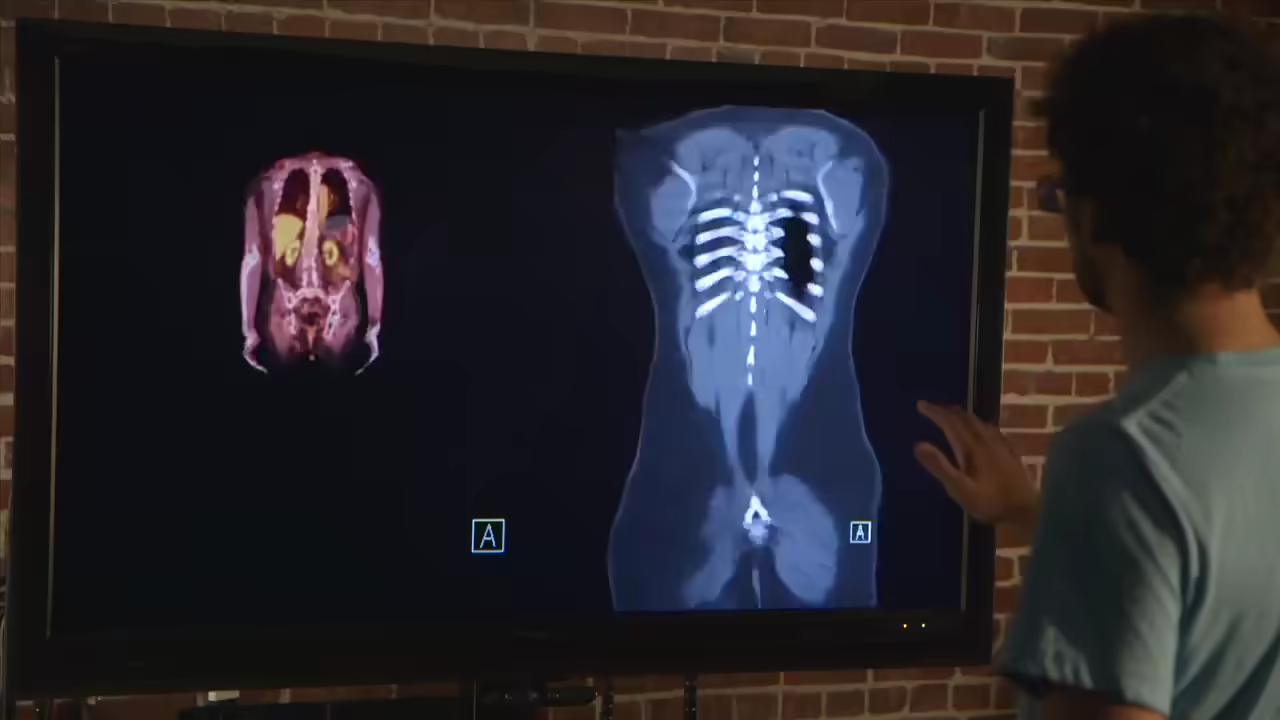

Spatial computing wasn’t just about tracking movement — it was about understanding presence. At Oblong, we designed environments where multiple people could share control, move data between walls, and gesture collaboratively across distance.

This required a new kind of UX thinking — less about screens and buttons, more about geometry, affordance, and social choreography. My design team worked closely with engineers to visualize how people, devices, and displays coexisted within a unified 3D coordinate system — one that treated walls, tables, and even physical objects as part of the interface.

Distributed Operating Environment (Mac Mini, Linux, iOS)

Radiology Demo

The Takeaway

Prototyping and invention were the lifeblood of Oblong. My role was to translate complex technical possibilities into experiences that felt intuitive and expressive — to design not for pixels, but for presence.

That philosophy has carried through my work ever since: making emerging technologies human by building, testing, and iterating until they feel right in the body.

John Underkoffler in Wired Magazine

HandiGlobe prototype: Multimodal control of an immersive spatialized data